US Crop Tour

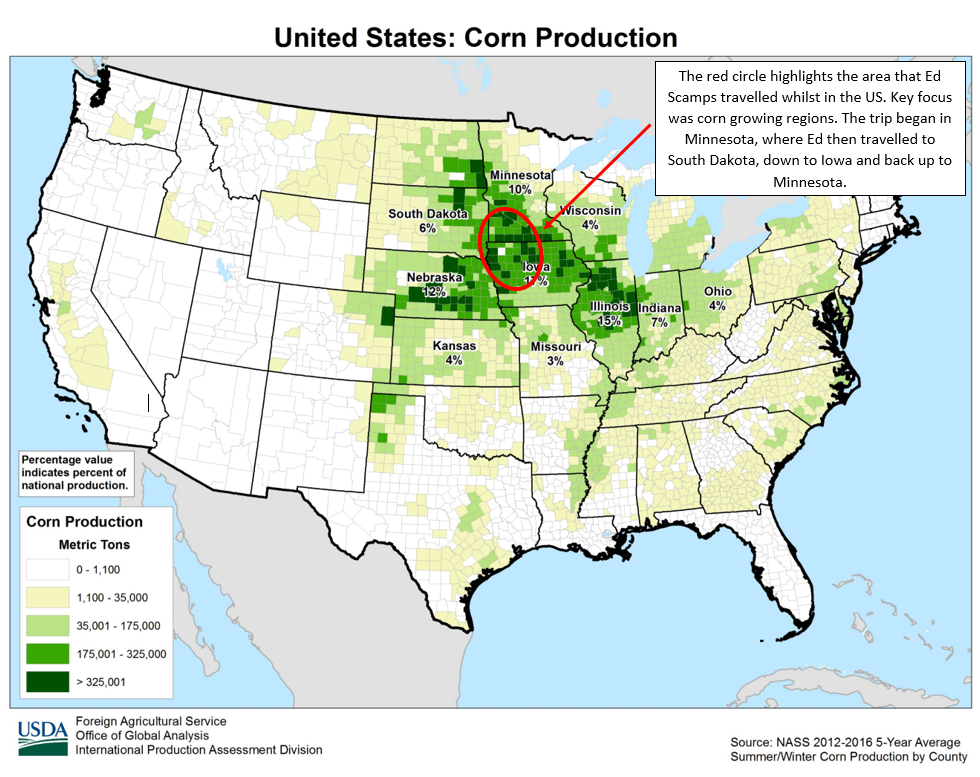

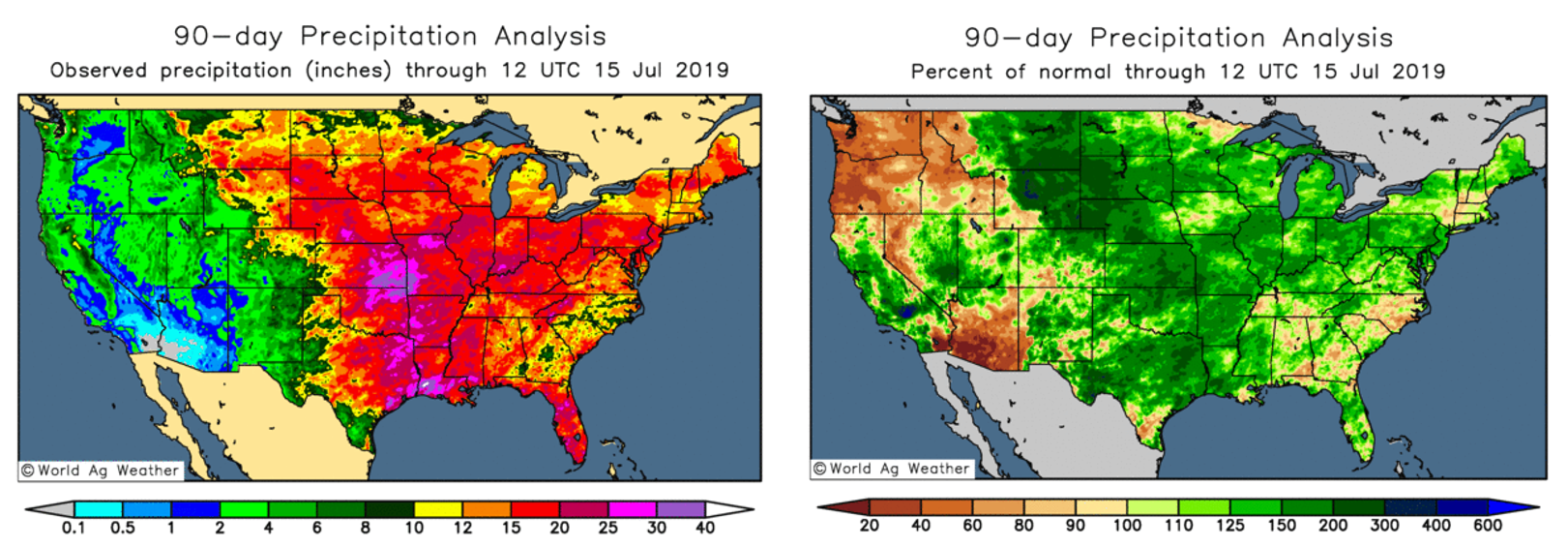

Ed Scamps, director of CloudBreak, recently travelled to the US for a week to see firsthand the detrimental effect that excessive wet weather had on corn and soybean plantings this year. The extreme weather began in March this year when a “bomb cyclone” created blizzard like conditions with hurricane force winds across the plains and Midwest. Rapid snowmelt following the storm led to flooding and concerns over crop damage for winter wheat that was about to come out of dormancy. Following on from this storm, many parts of the US were hit by thunderstorms and excessive rain right up until June. Row crops suffered significantly with many paddocks left fallow due to sodden soil and the lack of dry ground to commence fieldwork on. Planting was delayed and the US government subsidies were expected to come into play via the “Prevent Plant” program. This program is essentially an insurance policy that will pay out a grower should they not be able to plant a crop within the specified planting dates. Click here to see a worked example of how the MPCI coverage works.

How was your tour, where did you go and what did you see?

I flew into Minneapolis where I initially visited the old Minneapolis Grains Exchange Centre. Now just a historic relic, the building was once a hive of activity with traders buying and selling grain in the pit. The grains exchange is all electronic now, however, the significance of the building remains intact. Even though the US is declining in wheat production relative to the rest of the world, they are still so important for global price discovery. Minneapolis was always one of the smaller grain exchanges and obviously now we have Black Sea and Europe futures as well, but the US’s significant role in global price discovery is often why prices can be so US centric.

One of the first things I noticed in Minneapolis was the media coverage on the corn situation. All the newspapers were talking about corn and soybean plantings, it was front page news! Around Minneapolis there is a fair bit of spring wheat grown, and that shows since along the Mississippi river there are just mills upon mills. Most of the mid-west, however, is just purely corn and soybeans now.

After I spent a day in Minneapolis, I hired a car and headed south west towards Sioux Falls. Along the way it was very noticeable that it had been extremely wet, despite the heat while I was there, as most of the paddocks had this glistening sheen across them where water still lay upon the soil. It was clear that most of the crops were well behind development with the variation in progress highlighting the different planting dates. You could see how prosperous the area could be though, the roadside growth was just crazy. The quality of the soil in the area and abundance of water makes it one of the most fertile and productive food bowls in the world.

The other really noticeable thing throughout the area was the amount of infrastructure that even farmers had on their properties, some of which rivalled our smaller bulk handling sites. The farm set ups also had a strong nordic influence presumably from the mass scandinavian migration to the mid-west in the mid 1800s. The expanse of silos and storage options was so much bigger than what we have locally. Every single “middle of nowhere” town had a bulk handling system, even if they are only 10kms apart. It’s just nuts how BIG everything is! Grower co-ops are the big thing over there though. Some of the main ones I saw were Cooperative Farmers Elevator and New Vision Cooperation.

I continued my tour from Sioux Falls, south east toward Iowa. There were some patches of decent crops on the higher ground, but you could see that a lot of areas looked very saturated and boggy and crops in those areas were very immature. After talking to various growers (at their equivalent of a pub), I was told that corn was generally the first crop to go in and was given priority of the high ground, with soybeans being a later planted crop, they were hoping that low lying areas would drain off in time for a late planting spree. Inevitably this didn’t happen, and you can see the stark contrast in soybean vs. corn development. A lot of farmers did choose corn varieties with a shorter growing period. It was worth noting that they only have roughly 130 growing days and most farmers are thinking that their corn may not make it to harvest and is likely to be cut for silage.

I continued my tour east into Iowa before changing direction and heading north again toward Minnesota. It was astounding that all you can see is corn, soybeans or fallow paddocks. I would estimate that roughly 5-10% of all paddocks had been left fallow and many farmers had just picked the eyes out of the paddocks and only planted on higher ground or drier areas. The only animals I saw the whole trip were deer and skunks (all roadkill). The continuing theme throughout my trip was the sheer amount of infrastructure for grain. Once I turned north back toward Willmar (Minnesota), you could see a lot more water laying around with nowhere to go. This area used to be all glacial and there are many lakes. Most of the farmers in these areas are quite well to do, they all own nice pickups, lake houses, boats etc. A lot of this is possible as the US subsidises agriculture so heavily, especially corn and soybeans. Hence, why they all have nice houses, new machinery, infrastructure and all the rest of it.

I finished my tour on 4th of July, staying at a recreational lake in Minnesota. The fireworks were never ending. Overall, the trip was a great eye opener to the differences between Australia and the US, particularly with the amount of infrastructure and the abundance of natural resources.

For further reading in regard to the signifance of this years wet season in the US, please keep reading below.

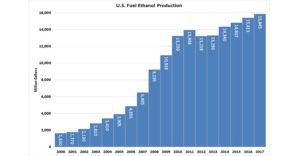

Last year, the US produced 366MMT of corn for which roughly 40% was used for biofuel production, predominantly ethanol, which overall has significantly increased since the early 2000s. Minnesota, South Dakota & Iowa account for approximately 33% of US corn production and the same three states produce over 6 billion gallons (22.7 billion litres) of ethanol each year, with Iowa being the leading ethanol state. As of 2017, there were 198 ethanol plants across the US producing a total of 16 billion gallons each year. Iowa has 42 ethanol plants, whilst Minnesota is home to 20 plants, and South Dakota has 2.

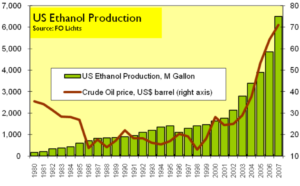

You may be wondering, why does the US grow so much corn and produce so much biofuel? It goes back to the oil crisis that occurred in the early-mid 2000s which saw oil prices skyrocket over a period of around 5 years ($25/barrel in late 2002 up to $147/barrel in 2008). There were many contributing causes for the price increase, however, one of the concerns was that the world was reaching “peak oil”. Peak oil is a term for when oil production reaches its maximum capacity. From here on, it is expected that oil production will only decline without the discovery of new oil fields. At this stage, it is unknown when peak oil will actually occur, by analysts expect sometime between now and 2030, with a high chance of it occurring within the next few years. The rise in oil prices spun the world into a frenzy with food, fertiliser and transport price spikes occurring throughout 2007-2008. To mitigate some of the price risk associated with oil, the US passed the Energy Policy Act in 2005, which mandated that biofuel must be blended into all vehicle fuel at a growing rate, to reach its target of 7.5 billion gallons of biofuel by 2012. In 2007, this target was then amended in the Energy Independence and Security Act which increased it to 36 billion gallons to be blended into vehicle fuel by 2022. For this target to occur, the US government has heavily subsidised corn production in order to entice growers to plant more corn acreage.